National park proposal dealt crippling blows

DELAWARE WATER GAP NATIONAL RECREATION AREA. But as supporters go mum, opponents worry the proposal is not fading away but gathering strength underground.

The prospect of a national park along the Delaware River was hit with a series of major setbacks after one its original architects quietly dropped its support.

The New Jersey Sierra Club backtracked right after electing a new slate to its executive committee in January. In a 13-4 vote, the committee rescinded the chapter’s support for redesignating the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area as a national park and preserve. In its spring newsletter the chapter said it will instead work to protect the recreation area through a new committee that will put “indigenous and community voices at the forefront.”

The New Jersey Sierra Club did not return messages requesting comment.

Another hurdle, perhaps insurmountable, is opposition by the Congressional delegation that represents the affected towns in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. That’s because it takes an act of Congress to create a national park, and it’s not clear who would sponsor such a bill.

Residents are telling lawmakers they don’t want their communities mobbed by the 600,000 extra visitors expected to visit a high-profile attraction like a national park. Hunters say they don’t want to lose hundreds of acres now open to them.

U.S. Rep. Matt Cartwright (D) of Pennsylvania’s 8th District said at least seven municipalities in Pennsylvania and 16 in New Jersey oppose the redesignation because of questions around hunting, fishing, wildlife management, outdoor recreation, property values, and eminent domain. “As a hunter myself, I also oppose National Park designation,” Cartwright told the paper.

This viewpoint is reflected across the river. “As I said from moment one, I believe that this matter required significant local input,” said Josh Gottheimer (D) of New Jersey’s 5th District. He told the paper that after talking to local mayors and soliciting local input over the last few months, he did not find the local support needed to move forward.

Tom Kean Jr. (R) of New Jersey’s 7th District also opposes the redesignation. The Warren County, N.J., commissioners were initially enthusiastic about the proposal but have since changed their minds.

The National Park Service itself is neutral, said Kathleen Sandt, public affairs officer for the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. She said the agency is not allowed to be a party in the creation of a national park.

The U.S. Constitution grants citizens the right to redress their government. It was citizens – not the government – who petitioned for a national park, Sandt said, and it is citizens who are now petitioning against it.

Bitter memories linger of the 1970s Tocks Island Dam debacle, when the federal government seized 70,000 acres along the river, uprooting thousands of families in the process, for a dam and reservoir that were never built (see Timeline, below).

“We have nothing to do with this,” Sandt said of the national park proposal.

PA chapter still supports park

The Pennsylvania Sierra Club continues to support the national park designation but isn’t saying what its next steps will be toward that goal.

The chapter’s new executive director, Thomas Schuster, cancelled an appointment to speak with the paper and instead sent an email that said: “The Pennsylvania Chapter of the Sierra Club continues to support the redesignation proposal and is a member of the Delaware River National Park & Lenape Preserve Alliance. As I am not the spokesperson for this Alliance, I would simply refer you to their website https://ourpark.org, which contains all the pertinent information about the proposal.”

It is not clear who is representing the alliance at this point. Those who have spoken for the group in the past have not returned messages, including Bob Fitch, the media liaison; John Kashwick, until January the vice-president of the New Jersey Sierra Club; and Jacqline Wolf Tice, an alliance steering committee member and an at-large delegate of the Pennsylvania Sierra Club’s executive committee.

John Donahue, who wrote the national park proposal and is its greatest booster, also could not be reached for comment. Donahue worked for the National Park Service for 38 years, including as superintendent of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, but he no longer serves in government. He currently heads up the nonprofit Pinchot Institute for Conservation and Three Rivers Environmental Consulting, a private business.

Chief Daniel StrongWalker of the Delaware Nation Lenape People of Anadarko, Oklahoma, also did not return messages. This tribe is federally recognized and has come out in support of the national park proposal. The local indigenous people, the Ramapough Lenape Nation, which is not federally recognized, strongly opposes it.

Campaign falls quiet

In his draft proposal for the redesignation, Donahue call the recreation area a “gem of our national heritage” that should be placed in “the jeweled crown of the national park system where it has always belonged.” In trying to sell the idea to a wary crowd at the Waterwheel Café in Milford, Pa., last July, he said a “grassroots” movement supported the proposal, to which someone shouted out, “Not a grassroots movement – there are 4,000 people against it.”

No one is out there now pitching for a national park. No advocate for the redesignation would speak with this paper.

The information freeze is leading some local residents to believe the proposal hasn’t faded away but has gone underground to gather strength.

“I don’t trust Donahue as far as I can throw him,” said Sandy Hull of Layton, N.J., of the group No National Park (nonationalpark.org). “If he won’t talk to you, that means they’re working to push this through somehow.” A member of Congress from out West might sneak the redesignation into an omnibus bill, she said.

Mineral extraction

Michaeline Picaro of Andover, N.J., a member of the Turtle Clan of the Ramapough Lenape Nation and wife of Chief Vincent Mann, agrees the proposal may pop up in some other guise.

Picaro noted that mineral extraction, including oil and gas, is allowed in national parks for the revenue it generates for the government. And she pointed to Donahue’s private environmental consulting business, Three Rivers, and his longtime support for mineral extraction on public lands as reasons to distrust his intentions. According to Donahue’s LinkedIn page, Three Rivers advises “law firms and nonprofit organizations on creating solutions to controversial issues” and recently advised Perkins Coie on the contentious Mountain Valley natural gas pipeline in West Virginia, in the area of a recently created national park that Donahue championed.

In 2021 Donahue told the podcast Below the Surface: The Secret Lives of Parks that, when he was superintendent of Big Cypress National Park in the Everglades, “We proposed and the Bush administration decided to move forward with the acquisition of the mineral rights.”

He continued: “The way I looked at it as the steward of the preserve was that if you buy the oil and gas rights and you control the oil and gas rights, there’s nothing but benefit for the people of the United States.”

‘We are still here’

Picaro said the federal government recognizes only one Lenape nation, the one based in Oklahoma, and not the tribe that originally inhabited the lands of today’s Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. But, she said, “We are still here.”

Picaro said the Ramapough Lenape do not know why the Lenape in Oklahoma have decided to support a national park that will irrevocably damage their ancestral homeland. “We were separated in the 1640s,” she said of the Western tribe. And after many years of massacres, wars, and sickness, she said, “We weren’t one people anymore.”

Picaro said a national park means more cars, more paved parking lots, more bathrooms and septic systems, more visitors’ centers -- all displacing the trees and stones and other sacred natural elements that her people venerate as their ancestors. “I do not want even one pebble moved,” she said.

She said the Ramapough Lenape are happy that people visit, enjoy, and learn about their ancestral lands, and simply want them to stay as it is now.

The clan has land deeds and agreements with the original Dutch settlers extending back to the 1600s that tie their people to the land, a territory that once extended from western Connecticut east to Long Island and south to Trenton, that the Oklahoma Lenape do not have. The Turtle Clan was from the area of Minisink Island, a Delaware River island between Milford and Dingmans Ferry, Pa. Picaro continues to build her people’s history through careful documentation, the preservation of artifacts, and the tracing of ancient trails marked by direction trees that still live and grow.

Maya K. van Rossum of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network wrote a letter to the alliance’s steering committee last year expressing concern about how the recreation area will be affected by the “massive new development” that surrounds any new national park. She also blasted them for sidelining the local Lenape.

“While Lenape representatives living in the Midwest have been included in the planning process, the Lenape Nation and tribes of our region, those that have an intimate, personal and enduring relationship with our River and watershed have not,” she wrote. “The perspective of the local Lenape tribes and people is essential and must be honored. Failure to include them in planning seems a dramatic oversight of high concern. At this time, based on what we know, the Delaware Riverkeeper Network cannot support National Park.”

‘Not enough factual information’

A possible path for national park advocates might be in simply giving local residents and their elected officials the information they’re asking for.

Towns that have passed resolutions opposing the redesignation say too many questions remain unanswered. “We simply don’t have enough factual information to make an educated decision one way or the other,” Sparta Councilwoman Christine Quinn told the paper.

Mayor George Harper of Sandyston said his township was the first to create and pass an opposing resolution, which it then sent to other towns, local school boards, and county legislators. The Sandyston resolution says the township is made up of approximately 70 percent state and federal lands. Stillwater, which adopted a similar resolution, says its township is made up of approximately 30 percent of state and federal lands.

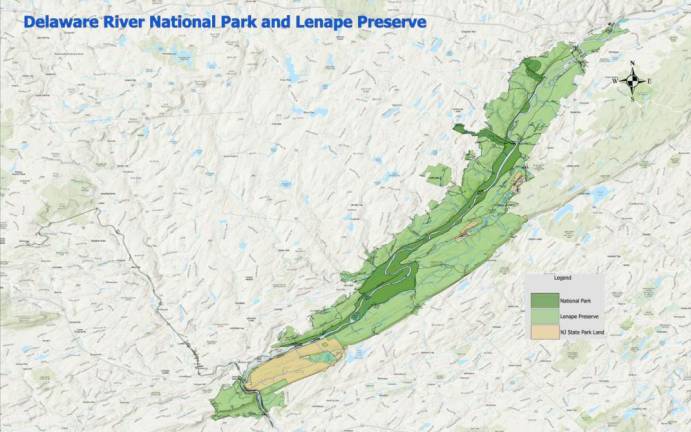

The resolutions say their townships will oppose a national park designation “unless and until a formal plan is presented offering information on the environmental, economic and agricultural impact of this proposed change; sources of funding; the fee structure and the plan for the implementation of fees and collection station locations; a map of the area depicting the location of the Lenape Preserve; the plans for any acquisition of additional private or public lands; and the impact this proposal will have on the residents.”

The quarter-billion backlog

In the meantime, the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area has a serious deferred maintenance backlog. Local opponents of the national park are asking how infrastructure in such need can handle hundreds of thousands of extra visitors.

Even without the national park designation, the recreation area attracts more than 4 million visitors a year. But it doesn’t attract federal money.

Sandt, the recreation area’s public affairs officer, said the deferred maintenance backlog, which mainly affects roads, is $259 million. The park’s annual budget? $10 million. All the agency can do is “whittle away” at the daunting backlog, Sandt said.

Some money has loosened up lately, she said, including $40 million from the Great American Outdoors Act and more from the infrastructure bill, which will direct another $19 million from the infrastructure bill to repair the Old Mine Road. Repairs to Route 209 began last year.

The national park proposal says the recreation area “currently welcomes as many visitors a year as Yellowstone on one-third of the budget,” and that “legislative language creating the park...will allow the necessary budget increases to accrue.”

Hull, of No National Park, considers that a canard.

She plans to fight to the end.

“If it gets to Congressional hearings,” she said, “we will be in Washington, D.C.”

Editor’s note: Do you want to see a national park at the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area -- or not? We want to hear your thoughts. Send them to njoffice@strausnews.com (New Jersey readers) or paoffice@strausnews.com (Pennsylvania readers), or post them online under this story.