Opioid deaths fall in region

Health. Data also show Naloxone usage by first-responders to treat opioid overdose has declined.

Public health data from New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania indicate that opioid-related deaths are on the decline throughout the region, signaling progress for addiction recovery programs and anti-opioid campaigns.

Recorded instances of Naloxone usage by first responders to treat opioid overdose also show a downward trend along with opioid-related hospitalizations.

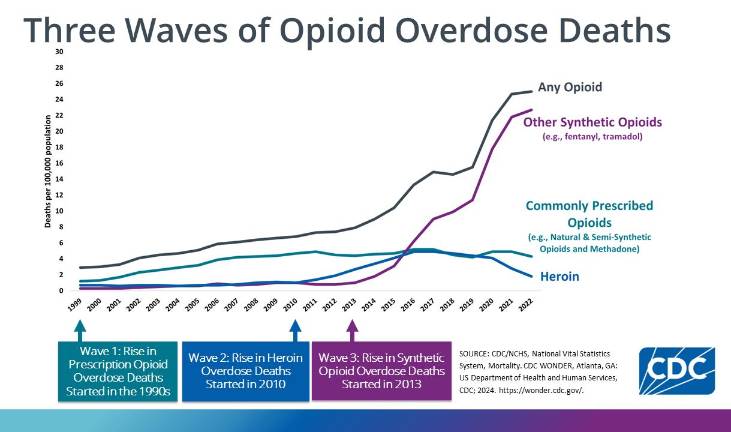

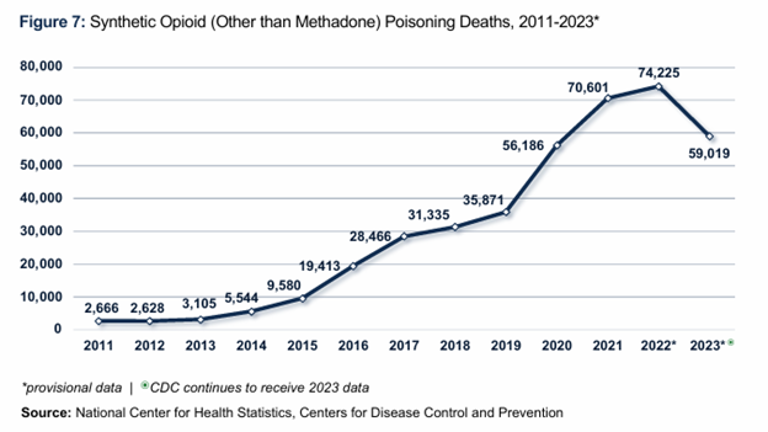

Based on data from the federal Centers for Disease Control (CDC), fewer opioid-related overdoses and deaths in the tri-state area are part of a larger national downturn in which 48 of 50 states reported nearly 27 percent fewer deaths from February 2024 to February 2025.

Crisis close to home

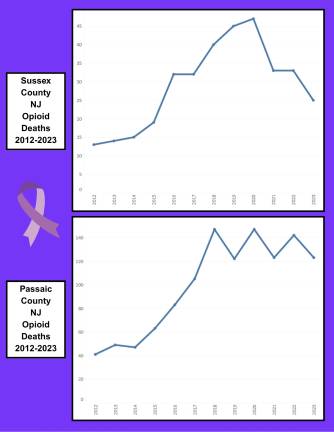

The data in northern New Jersey shows that in Sussex County, opioid-related deaths peaked at 47 in 2020, declining to 25 in 2023; an overwhelming majority of those deaths were attributed to fentanyl. The New Jersey Department of Health Overdose Data Dashboard shows that recorded Narcan uses in Sussex County also declined on the whole, from 113 in 2020 to 56 in 2024; there have been 15 recorded uses to date in 2025.

Passaic County has seen a similar decrease in Naloxone administration, declining from a peak of 737 recorded uses in 2022 to 455 in 2024, with 147 thus far in 2025.

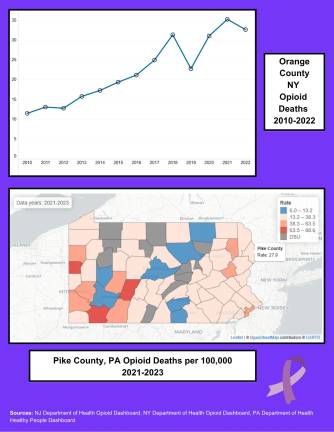

The New York State Department of Health also maintains an Opioid Data Dashboard, which tracks metrics for the state, its regions and individual counties. Opioid-related deaths in Orange County peaked at 137 in 2021, but came down slightly to 124 in 2022, the latest year recorded in the database.

Narcan usage also came down in Orange County, from a high of 360 recorded doses administered in 2020 to 284 in 2023.

In Pennsylvania, the Department of Health tracks opioid-related deaths as a ratio per 100,000 residents, with a PA Healthy People objective goal of having 13.1 or fewer deaths per 100,000 by 2030. The data for Pike County shows that there is still work to be done to reach that goal; there have been an average of 29.12 opioid-related deaths per 100,000 each year in Pike County since data tracking began in 2017, with a high of 39 per 100,000 in the 2020-2022 metric frame.

Funding fight to change lives

Much of the recent funding for community-based recovery programs and drug task forces comes from opioid lawsuit settlements from the manufacturers of prescription opioids. Pennsylvania manages its funds through the PA Opioid Misuse and Addiction Abatement Trust, which distributes money to Single County Authority (SCA) organizations throughout the state to develop, fund and maintain programming that supports addiction recovery. Additional funding and oversight come from the Pennsylvania Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs.

In Pike County, the Carbon-Monroe-Pike Drug & Alcohol Commission serves as the SCA for all three counties. The council is a non-profit council appointed by the commissioners of those counties, charged with administering funds and planning, coordinating and evaluating drug and alcohol services.

The Pike County Substance Abuse Task Force is the Pike County arm of the Carbon-Monroe-Pike Drug & Alcohol Commission. It offers educational resources and prevention programs for all ages, coordinate inpatient and outpatient treatment plans, including funding treatment for those without insurance, and focus on reducing stigma and supporting recovery efforts with community-based services.

New York’s opioid settlement funds are administered by the Office of Addiction Services and Supports (OASAS). To date, New York State Attorney General Letitia James has secured more than $3 billion in settlement funds for the state’s prevention and treatment efforts. Her office released a statement on July 10 outlining the $38.7 million in funding that will come in from new settlements with eight drug makers.

“While communities throughout our state continue to suffer from the opioid crisis, these resources will help us begin to heal,” James’s statement read in part, “I will continue to work to hold those responsible for the opioid crisis accountable and ensure that New Yorkers who have been most affected get the support they need.”

Orange County uses its share of funding from OASAS to support a variety of treatment, education and prevention initiatives. Many of these initiatives are designed with an innovative “meet people where they are” approach, including collaborating with community partners to co-locate and expand services within existing programming. That includes adding school-based Substance Abuse Prevention Specialists within eight of the county’s districts, providing mini-grants to local non-profits to support and expand recovery housing, and a unique pilot to co-locate a peer recovery specialist within emergency medical services.

“That Peer is within the New Windsor EMS department and responds with EMS when someone has had a non-fatal overdose,” said Rebecca Sheehan, Orange County Director of Public Information. “The goal is to engage the individual in real time and link them to treatment immediately. The individual is often physically sick and embarrassed. A Peer, someone who has walked in similar shoes, has been proven to be more effective in engaging individuals in these situations.”

Orange County has also expanded other services, including Naloxone training, Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) resources, anti-stigma campaigns and maintaining a 24-hour crisis phone hotline for all and a 24-hour crisis text line for teenagers.

A Youth Peer Specialist is also available to young adults struggling with substance abuse, and funds were granted to the Catholic Charities of Orange County to build a countywide youth coalition promoting prevention and awareness.

Settlement money has also been used to fund a Senior Caseworker to monitor drug trends, a Peer Services Coordinator for first responders struggling with their own mental health or substance abuse concerns, and a Community Engagement Specialist.

“We haven’t had some of this programming before, and it’s allowed us to expand our outreach to populations like youth and first responders with a dedicated and strategic approach,” Sheehan said. “Many community members may not know what’s available or how to access what’s available. We see this as an access to care issue. This is why we funded the Community Engagement Specialist, a position which is critical to increasing access to care.”

New Jersey has also received a share of opioid lawsuit settlement funds, with the first payments coming in 2022 and scheduled to last until 2038; the funds will eventually total more than $1 billion. State Attorney General Matthew Platkin issued a release the same day as James in New York, indicating that New Jersey will receive up to $19.8 million from the most recent settlements.

“We expect state partners to use these funds responsibly to alleviate the suffering in the wake of this manmade substance use disorder epidemic,” Platkin said in his statement.

Although a plan was adopted by the Sussex County Board of County Commissioners in August 2023, full programming using settlement funds has yet to be developed. Settlement funds have, however, been slated for a long-standing community recovery nonprofit organization, the Center for Prevention and Counseling in Newton, to provide youth educational and prevention programming.

While not directly funded by opioid settlement funds, the center is at the forefront of recovery and prevention education efforts in Sussex County, including being the lead nonprofit partner of the Community Law Enforcement Addiction Recovery (C.L.E.A.R.) program. C.L.E.A.R. provides immediate 24/7 support through a phone and text hotline.

Passaic County uses some of its settlement funding for the Passaic County Center for Addiction Recovery Education & Success (CARES) program, a partnership with the Passaic County Division of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Passaic County Sheriff’s Office and the Morris County-based non-profit Prevention is Key. Efforts focus on peer-to-peer recovery support, Naloxone education and access, and include in-office and mobile services as well as a 24/7 peer support line.

Passaic County CARES’ new recovery center, in Pompton Lakes, celebrated its grand opening Wednesday, July 30.

N.J. budget diversion

Platkin’s recent statement about the opioid lawsuit settlement funds heralded good news for recovery programming in New Jersey, but he and many others remain concerned about the diversion of $45 million from the settlements into the state hospital system. This diversion was not part of the original proposed budget, nor was it accounted for in the New Jersey Opioid Recovery & Remediation Advisory Council’s five-year strategic plan released this spring.

On June 30, hours before New Jersey’s fiscal year 2026 budget was passed and signed by Gov. Phil Murphy, Platkin’s office released a scathing critique of the proposal to divert the money from the settlement fund into the hospital system for “undisclosed uses.”

That proposal stayed in the budget when it was signed, and Platkin, while not denying that hospitals need funding, called the action “a slap in the face to every family who lost a loved one in this devastating crisis.”

“My office fought for years against companies who profited off the deaths and addiction of thousands upon thousands of New Jerseyans,” the statement said. “When we announced these settlements, I stood with Governor Murphy and promised these settlement dollars would go towards evidence-based solutions to help those struggling with opioid addiction - not to pad the state’s coffers.”

The New Jersey Opioid Settlement Advisory Council released an open letter to state leaders July 8, also criticizing the diversion.

“The irony here is hard to ignore,” the letter says. “Taking money away from overdose responses and addiction services will send more people into crisis and further overwhelm an already strained healthcare system.”

Though the data shows a decline, it also indicates that the opioid crisis is far from over in the tri-state region. It’s this further testimony in the Advisory Council’s letter that sums up the importance of the settlement funding and its impact on recovery efforts:

“We have seen the difference that state funding can make in our collective work, and how it can make a difference between whether someone lives or dies.”

We have seen the difference that state funding can make in our collective work, and how it can make a difference between whether someone lives or dies.”

- New Jersey Opioid Settlement Advisory Council