Snapping out of it

BENEFITS. Food pantries and other local organizations helping low-income residents brace for the end of the federally-funded SNAP Emergency Allotments.

After nearly three years of providing eligible households with extra money for groceries, the final SNAP Emergency Allotments were dispersed in February.

Since March 2020, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) households have received a second payment each month. The additional funds either paid the difference to bring a household’s monthly total to the maximum benefit or provided an extra $95 – whichever amount was greater.

For example, the average New York SNAP household in 2019 was a family of two, receiving $230 in SNAP benefits each month. That family was bumped to the maximum benefit for a two-person household, which is currently $516, by receiving a second payment of $286 in an emergency allotment each month.

Alternatively, if a four-person family was getting $900 a month or the current maximum benefit of $939, they would get a second emergency allotment of $95.

Thousands of low-income residents benefited from the emergency funds. As of last November, SNAP supported:

• 2,138 households, totaling 4,096 people in Sussex County, N.J.

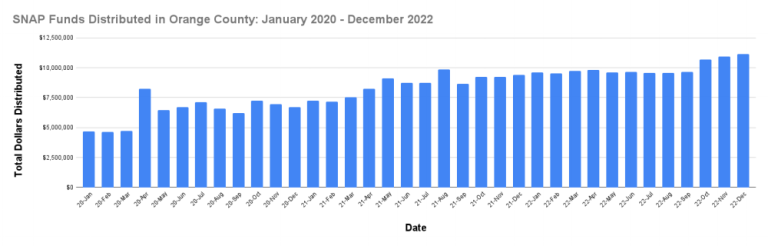

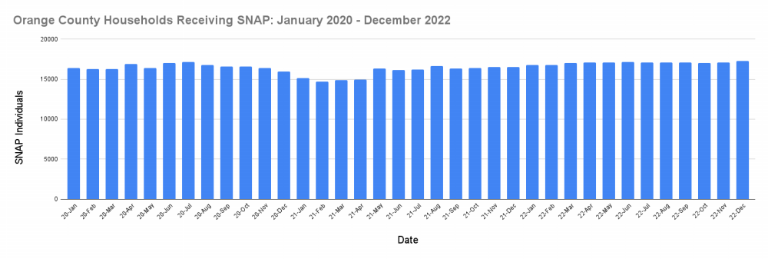

• 17,108 households, totaling 39,944 people in Orange County, N.Y.

• 35,847 households, totaling 73,576 people in Passaic County, N.J.

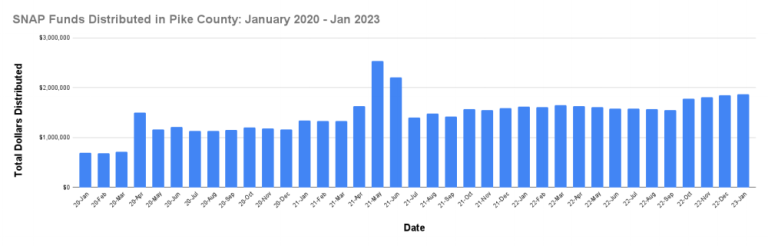

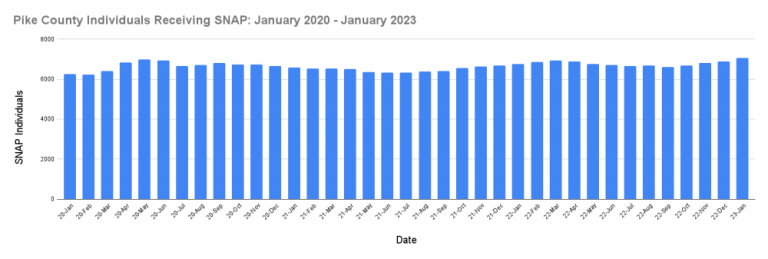

• 6,807 people in Pike County, Pa.

Now, many are struggling to figure out how they’re going to put food on the table.

“Originally I was getting $16 a month. Now what can possibly buy for $16 a month? Two cups of coffee, maybe?” said Judith Koerner of Matamoras, Pa.

When the coronavirus pandemic began, her SNAP funds jumped from $16 to the maximum monthly allotment for a single-person household, $194 in 2020 and $281 in 2022.

Koerner, 81, is disabled and her only source of income is Social Security. In the past year, she underwent chemotherapy, was hospitalized with COVID-19 and needed iron infusions after an internal bleed. She uses a walker and has a friend go grocery shopping for her.

“I have a lot of medical problems,” she said. “So I can’t do my own shopping and I can’t do cooking.”

Usually, she gets pre-made microwavable entrees. But three microwavable chicken tender meals from ShopRite cost more than $10, she said. That’s nearly half of her usual SNAP benefit, which has increased during the years to about $23 a month.

She’s not sure what she’s going to do to pay for groceries. It’s hard to get to the food pantry because of her disability, and she is bogged down by medical bills.

Koerner does get five meals delivered weekly from Meals on Wheels, but she doesn’t particularly look forward to eating them.

“They are horrible,” she said. “But you know, beggars can’t be choosers.”

Rising costs

Diane Masucci, 77, of Harriman, N.Y., collects Social Security and works part-time at the Woodbury Common to support herself and her 12-year-old grandchild. She usually receives about $23 a month in SNAP benefits, but with the emergency allotments, that total was raised to the maximum benefit for a two-person household, which this year is $516.

“And that’s ended,” she said. “And they said I don’t qualify for anything because I earn too much money.”

She takes home $1,240 in Social Security and $400 in child support each month, much of which is eaten up by rent. Masucci works five to 15 hours weekly at Woodbury Common to pay the bills: electricity, car insurance, school lunches and internet service so her granddaughter can complete her schoolwork.

Masucci and Koerner were unable to set aside a portion of the emergency funds to get them through the next few months, largely because of rising grocery costs. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the price of groceries has increased more than 20 percent in the Northeast from January 2020 to January 2023.

“It’s impossible to try to save from one month to the next,” said Koerner. “It’s not that I buy a lot of food, it’s that the food is so expensive.”

Rising need

While the emergency allotments are ending, food insecurity is on the rise. The Sussex County Department of Health and Human Services saw a 45 percent increase in SNAP applications between 2021 and 2022.

Local food pantries are hustling to keep up with the demand.

The Ecumenical Food Pantry of Pike County saw 50 more families in January than it did a year earlier.

“We definitely know that most of it is because they’re going to be losing more of their SNAP program,” said the pantry’s director, Nancy Potter. “I think unfortunately, they got used to it ... and now all of a sudden, it was a shock when they realized it was going to end.”

The Sparta Community Food Pantry, which feeds 2,000 households throughout Sussex County and beyond, saw demand increase 40 percent between 2021 and 2022. The pantry’s board president and director, Valerie Macchio, estimates that this year, the pantry has seen additional 30 people each week as a direct result of the reduced SNAP benefits.

“From what I’ve seen from January to February ... we had a couple of days where we saw over 100 people a day,” she said. “That’s huge.”

New Jersey SNAP recipients are seeing some extra assistance with the transition. Gov. Phil Murphy signed a bill in February to provide all SNAP-eligible households with a minimum of $95 a month, supplementing a household’s federal SNAP benefit with state funds to pay the difference. The minimum federal monthly benefit is $23.

Low-income homes in other states are bracing for a bigger adjustment.

“I need help. But I gotta keep myself going. My most important thing is to make sure I live a little bit longer to get (my granddaughter) grown,” Masucci said. “I really don’t know what I’m going to do. I will need (to work) 15 hours a week to go to the grocery store. By the time I pay my rent and my bills, I don’t have anything left over for food, except what I earn at work.”

It’s impossible to try to save from one month to the next. It’s not that I buy a lot of food, it’s that the food is so expensive.” - Judith Koerner, 81, of Matamoras, Pa.