Slow pivot: The surprisingly gradual art of reinvention

Warwick. How a Harvard-trained desk jockey economist turned into a cattle farmer.

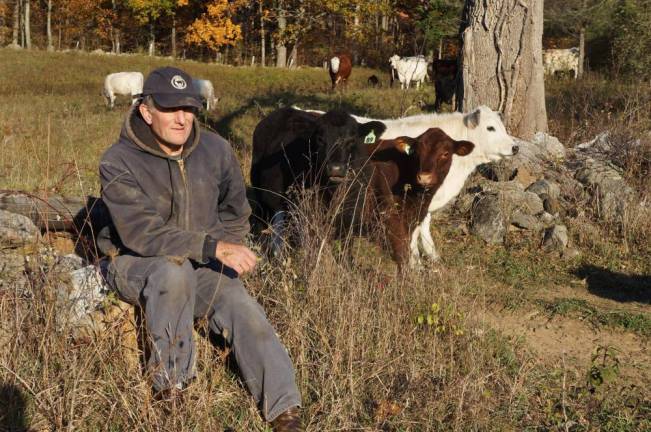

Will Brown’s sprawling grass-fed beef farm in Warwick, N.Y., is just 50 miles northwest of Manhattan, but a galaxy away from the city. Home is a restored Depression-era farmhouse, surrounded by meadows where sheep and cattle graze.

On a spring day, wearing a torn polo shirt and sturdy jeans, the 71-year-old farmer offers me a tour. Unhooking a metal cattle fence, he leads the way along a muddy trail through a cow pasture, the air still, the only sounds the chirping of birds and the long grass rustling in the wind. Suddenly, I jump – a giant, terrifyingly fat black snake is slithering underfoot. “Snake!” I scream.

Will, a few steps ahead of me, looks laconically over his shoulder without stopping. “What color?”

“Black! A huge black snake! What is it?” I’m shrieking now.

“Black snake.” He’s a man of few words. “That’s what it’s called.”

I scramble through the muck after him, trying to keep up.

We reach his battered Suzuki and he takes the wheel to show me the rest of his Lowland Farm, which stretches out over a thousand acres and straddles the New Jersey border.

‘An hour out of Manhattan and gone back a century’

Will Brown certainly never set out to be a farmer. The son of a Swarthmore economics professor, he had attended private schools before heading to Harvard and then joining J.P. Morgan after graduation. He and his wife were searching for an affordable weekend house in the mid-1980s when, at the end of a long day, the realtor convinced them to take a look at an old, failing dairy farm. A foot of snow carpeted the ground. It was like entering a time capsule.

“You go down this half-mile dirt driveway, and it’s an old farmhouse. In there was the wife—the heat didn’t work, so they had a kerosene heater. And the minister from the Presbyterian church was there, in his black frock,” Brown recalled. “I thought, We’ve gone an hour out of Manhattan and gone back a century.”

He was immediately charmed. Besides, “it was cheaper than any house in Connecticut.”

They bought the place, renovated it and retreated there on weekends.

It took decades, and an endless progression of incremental steps, for that weekend getaway to transform into a full-time profession. It was such a gradual process that Will barely realized it was happening.

Rounds on the farm, not the golf course

A few weeks after we first toured the property, I join Will on his daily rounds. It’s a steamy summer Sunday, when his erstwhile colleagues would be out playing a round of golf or lingering over brunch in the Hamptons.

Instead, I’m riding shotgun in Will’s mud-caked open-air utility vehicle, rounding up cows and herding them to new pastures. Each pasture is marked with a thin metal fence—electrified with 8,000 volts coursing through it. I watch as he cuts the power on one piece of fence, shoos the cows out, then reconfigures the enclosure and flips the power back on.

“Don’t you worry you’ll get shocked?” I ask.

He shrugs. “Happens all the time.”

Will slaps cows on their flanks, claps his hands, yells “Ho! Ho!” then jumps back in the vehicle to lead the way to an adjoining pasture. Within a few minutes, the herd is following us obediently, like so many 1,400-pound puppy dogs trotting behind us.

Applying economics to the difficult business of farming

It’s hard to imagine how a Harvard-trained desk-jockey economist could pivot so comfortably into farm life. Yet when I ask Will about it, he describes the change as more of a continuum. In his second career he uses all of his previous experiences, he says, even though, to an outsider, they seem completely disconnected.

Part of the challenge and the appeal for Will is to apply his economics brain to the notoriously difficult business of farming. Another attraction is that he oversees every element of the farm operation, from birthing cows to selling steaks, whereas in his corporate job he was one cog in a giant organization. “You do whatever your specialty is. You only see your piece of business. This had more appeal.”

Will’s reinvention was a gradual process. Perhaps the most important reason for his success is that he began moving toward his new life before he consciously realized he was leaving the old one. He scaled back his consulting business while simultaneously increasing his involvement on thearm. He slowlfy adjusted to the different rhythms of life, rising with the sun — before 5 a.m. in the summertime—without so much as an alarm clock, even though in his J.P. Morgan days he had to force himself out of bed when the alarm rang at 6 a.m.

As I take my leave, eager for a shower and air conditioning, Will pauses to see me off. His worn T-shirt is stained with sweat, and his shoes are caked with cow dung and mud. There’s no trace of the one-time Ivy League economist in suit and tie. The temperature is fast approaching 90 degrees, even though the early morning sun is barely peeking through the trees.

He looks happy.

Excerpted from “Next! The Power of Reinvention in Life and Work” (2023) by journalist and author Joanne Lipman of Warwick.

Part of the challenge and the appeal for Will Brown is to apply his economics brain to the notoriously difficult business of farming. Another attraction is that he oversees every element of the farm operation, from birthing cows to selling steaks, whereas in his corporate job he was one cog in a giant organization. “You do whatever your specialty is. You only see your piece of business. This had more appeal.”