This week, this column was written by my friend Vernon historian Ron Dupont.

Sinkholes on Route 80 in Wharton have caused highway closures, traffic havoc and detour nightmares in the past six months.

Located near the Route 15 interchange, the sinkholes had a surprising cause: an old iron mine.

Many wondered: iron mines? In New Jersey? When was this? Didn’t they have to file plans, permits, maps? When did they close? Didn’t they have to seal them up? And what genius thought it was OK to build an interstate highway over a #$%@! old iron mine?

Indeed, though it doesn’t have iron mining and smelting today, from the 1700s to the early 1900s, New Jersey was one of America’s biggest producers. Hundreds of mines fed forges, furnaces and mills, producing all sorts of iron and steel goods.

The switch to cheaper anthracite coal fuel and Great Lakes iron ore -all westward - brought this era to an end in New Jersey.

And while there are hundreds of iron mines spread across northern New Jersey, Morris County was the 800-pound metallurgical gorilla.

The area where the sinkhole occurred is a virtual rat’s nest of old iron mines: the Richards, Baker, Huff, Hurd, Johnson Hill and Orchard mines all operated here, spitting out tens of thousands of tons of ore decade after decade in the 1800s.

Route 80 was built atop the Mount Pleasant Mine. It was one of the oldest, biggest and best mines in the state. Started in 1786, it was owned by iron pioneer Moses Tuttle.

Later operated by Guy M. Hinchman, the mine was bought by William Green and Lyman Dennison, partners in the Boonton Iron Works. Ore was smelted to make nails at the Boonton works.

Its next owner was the new proprietor of the Boonton works, James Couper Lord (his estate later donated a park named in honor of his daughter, Grace Lord Park).

For much of the late 19th century, Mount Pleasant was one of the most productive mines in the state. Ore was considered good if it had 50 percent iron; Mount Pleasant’s sometimes ran closer to 70 percent. It employed as many as 400 men and even had its own railroad spur.

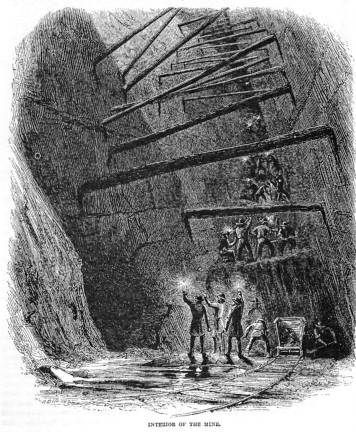

Unlike what you might imagine, such mines were like giant underground galleries or slits, tilted about 45 degrees, where the narrow ore body traveling down into the earth was extracted from between rock, above and below (see illustration from 1859).

These open “stopes” could go for hundreds of feet both horizontally and vertically. The Mount Pleasant mine was ultimately 3,000 feet long and 1,400 feet deep (the lowest point was almost 350 feet below sea level). It was heavily timbered, but timber only lasts so long.

It closed in 1896 when it was no longer profitable to operate. In its lifetime, some 400,000 tons of iron came from it.

Old reports say the mine equipment was sold and the plant demolished. The shaft openings were presumably blocked off/sealed in cursory fashion.

Were there permits, maps, reports, plans filed as to the mine’s location underground, how it was closed, etc.? No, no and no. These were the days of red-blooded laissez-faire capitalism. We don’t need no stinkin’ plans or permits.

Fast forward 60 years: highway officials are planning the new interstate highway system, limited-access freeways with no traffic lights or grade crossings. Route 80 between the George Washington Bridge over the Hudson River and the Delaware Water Gap was planned by the mid-1950s.

Some of it was built on existing highway routes, while other sections were entirely new. It wasn’t completed until 1973.

The section in question, between Denville and Wharton, was completed and opened in November 1959.

Did the highway engineers way back when know about the mine when they built it? Were any openings even visible?

There seems to be a consensus among Wharton old-timers that the little pond in the area just north of East Dewey Avenue is in fact the collapsed and flooded southern end of Mount Pleasant Mine. So people knew the mine was there.

Then too, the amount of planning and land acquisition for a project of this scale required extensive review of maps, deeds and other documents. Even a cursory review would have shsown that they were going right over an old mine.

My guess? Yeah, you bet they knew. Like everything else, Route 80 was built on lowest bid, a timetable and a budget. If any shafts were still open, they likely plugged them.

If not, they probably figured the mine was deep enough and buried long enough that they could roll the dice and be OK.

Either way, they’d be long gone by the time any problems materialized (true that).

What they maybe didn’t know - you have to dig into old geology reports like some nerdy historians do - was that as early as 1855, the Mount Pleasant ore body had been mined to within 40 feet of the surface. About the length of a telephone pole.

Even if the shaft openings were sealed, the vast old stopes remained open not far underground. Safe enough to build an interstate highway over? Hmmm.

Rotting timbers, subterranean rockfalls, the occasional little earthquake. And bingo: a sinkhole. They are not uncommon in northern New Jersey, with many occurring over the years.

They just never happened in the middle of an interstate highway before.

Just fill the damn thing with concrete, some say. You could. But I did the math and it’s not pretty: 400,000 tons of ore plus waste rock = about 6 million cubic feet of material = about 2,000 truckloads of concrete to fill the void.

If you want a real thrill, hunt down some of the highly detailed old maps of Morris County’s iron mines, and see what lurks below some of these heavily developed, ever-building areas.

The Route 80 sinkhole might have been the first one to cause major chaos. But it might not be the last.

Bill Truran, Sussex County’s historian, may be contacted at billt1425@gmail.com