We recently recognized an Army soldier from McAfee, Roy Sisco, who was killed in action in Belgium near the end of World War II.

We also investigated where he was buried and some of the details of his ultimate sacrifice for our nation.

As Memorial Day approaches, we find more about the Sisco family and their lengthy time in America. Information comes from reader Debbie Woch.

This began with Woch looking for information about the Windham Forge article. She and her husband live in Stockholm.

Her grandmother Ethel Sisco had found a connection to the family as far back as the Revolutionary War with an ancestor Tannie.

Research on Tannie was provided by the always ready, very informative Lisaann VanBlarcom Permunian, who is a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) and a member of the Vernon Historical Society.

Permunian has put in many years of valuable historical research and graveyard work.

As an aside, in recent years, the number of newspapers has fallen mainly because of the internet. A hundred years or so ago, there were even more newspapers. For example, there were the Sussex Register, the Sussex Independent and the Wantage Recorder, all published in Sussex Borough, and the Signal in Sparta in the late 1800s.

In Passaic County, running from 1865 through 1871 were the Paterson Daily Guardian and Falls City Register, according to the Library of Congress. In the Guardian, dated Jan. 5, 1871, was an article titled “Tannie Sisco, the Revolutionary War Drummer Boy from Macopin.”

As it was told, Nathaniel Sisco, commonly called Tannie, was the son of John “Fighting John” Sisco. This was during the Revolution.

Tannie was 14 and living with his parents at Macopin. His father was of the Tory persuasion and a supporter of the Cowboys. During the Revolution, Cowboy was a term for those who stole cattle and supplies, then sold these to the British in New York City.

Since the Cowboys were in the service of the British troops, Tannie refused to go with them, being impressed with the idea that his services belonged to the American cause.

His father flogged him with a knotted rope to compel him to go. His mother interceded for him, but his father replied “he would flog him within an inch of his life” and continued beating him until the boy consented to go, with a mental reservation, as he afterward stated.

Tannie went to bed and, on finding the rest of the family asleep, arose and dressed himself. He was in his tow pantaloons which, with his shirt and hat, were all the clothing he had. (Tow pantaloons refers to trousers made of tow cloth, which is a coarse and loosely woven fabric made of flax or hemp. These were worn by laborers and enslaved people in the 1700s and 1800s).

He started by foot for Hackensack, a distance of 25 miles. He had never been farther on the road than Pompton and arriving there was at a loss about which direction to take. He took the left road, which proved to be the right one, and acknowledged the guiding hand of Providence, which led him on the direct route to Hackensack.

At Red Hill, he was stopped by a sentinel, who commanded him to lay down his arms and give the countersign. Tannie did not understand what he meant but told him he wished to go to Hackensack to join the American forces.

The sentinel told him to pass on but that he would be stopped again, and when this occurred, he must raise his left arm. He soon had occasion to do so and passed unmolested and reached Hackensack at daylight.

He asked for Capt. Outwater of the Bergen County Militia who, he had heard, was located there with his company. On approaching the house to which he was directed, the captain looked from his window and asked who he was.

Tannie replied, “I’m Fighting John’s son.” The captain knew who Fighting John was and directed Tannie to a certain tavern in the village, which had a sign-board with a horse on it. He was told to eat there and to put the cost on the captain’s account. While at the table Tannie fell asleep and was put to bed.

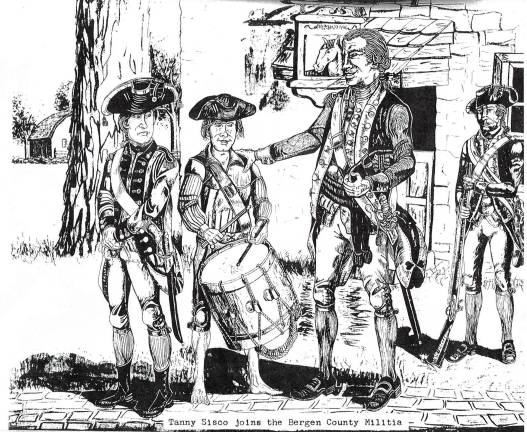

Tannie was soon aroused by the beating of a drum. He went out and while standing near the drummer, Outwater approached him and asked what he thought of it. He replied that he could drum better than that fellow.

The captain handed Tannie the drum and told him to try. He did so and gave such satisfaction that the captain gave him a dollar and dressed him in a suit of American regimental clothes.

A few days after this, Fighting John came to Hackensack and demanded his boy. Outwater replied that Tannie belonged to him now and if John made any disturbance, he would detain him also.

Tannie then approached his father, and they had some conversation after which the father left for home and Tannie was installed as drummer boy, the position he held until the close of the war.

Afterward, Tannie returned home to his parents and did what he could for their support until their death. During the war, he had regularly sent his wages to his parents for their support.

He lived to be an old man. His occupation in the latter part of his life was to guard cattle, which were turned out to pasture on the mountain where he lived. He would often relate, with pride, his war experience and called his residence Macopin, the Seat of Government.

Here was an instance of true patriotism where a boy of but 14 years and of Tory parentage, with Tory surroundings could not be induced to fight against his country but was impelled by a pure sense of duty, without any hope of reward, engaged in the service of his country, at the same time, giving all his wages to his Tory parents. He deserved a place in history which had never been given to him.

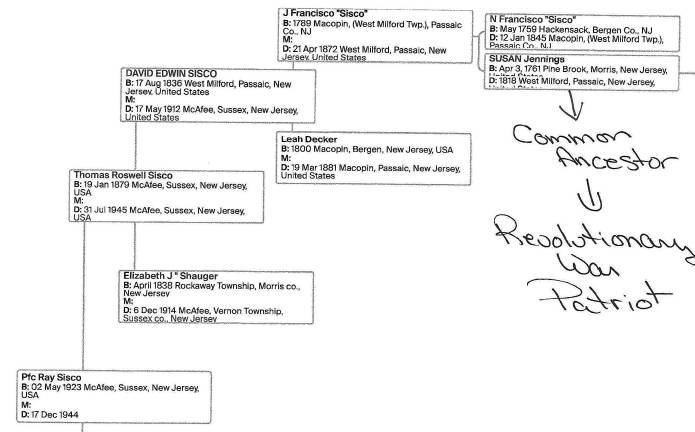

As can be seen on the image of the ancestry of Roy Sisco, he is a direct descendent of Tannie. Both were patriots and, yes, deserve our humble regards for their service.

Bill Truran, Sussex County’s historian, may be contacted at billt1425@gmail.com